Picture of the week

| Previous weeks |

Jan

26, 2014 Jan

26, 2014 |

Jan

12, 2014 Jan

12, 2014 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Nov

17, 2013 Nov

17, 2013 |

|

|

|

|

Oct

20, 2013 Oct

20, 2013 |

|

|

Oct

6, 2013 Oct

6, 2013 |

| Older |

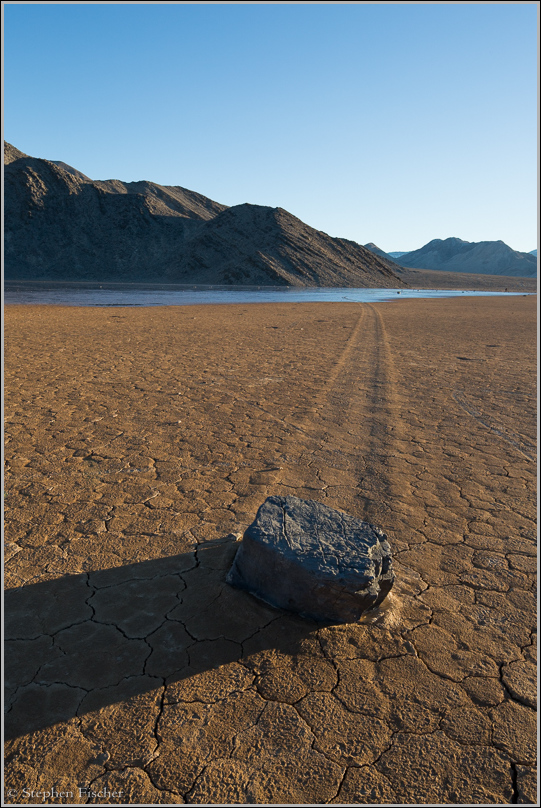

Theory of the moving rocks on the Racetrack at Death Valley

The image above was captured last week at the Racetrack, a remote dry lake bed near the northwest corner of Death Valley National Park. This location is famous for the mysterious moving rocks like the one above that no one has witnessed in actual motion. There have been many theories, some more humorous than serious (i.e. secret alien landing sight markers). The dominate theory has been that during the colder and wetter winter months, after a cold rain with possible sleet and ice, the winds can get strong enough on this playa to cause the rocks to start sliding. The challenge with this theory is that the winds would need to overcome the initial static friction of the rocks as sitting on the playa. Efforts to test this, have not been able to substantiate this theory. Some of these moving rocks are also quite large, some weighing over 10 pounds, which further aggrevates this theory. The other mysterious situation is that some of the rocks tracks don't start from the edge of this dry lake bed, but further in. Raising the question of how did the rocks get on the playa in the first place without leaving marks?

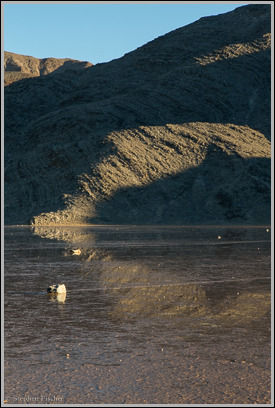

When visting this playa the last time, after camping the night before in stormy and below freezing temperatures, it dawned on me on how the movement of these rocks comes about. In this visit I noticed water had accumulated at the southwest corner of the playa, and was slowly drying up there last. This corner also tends to be where most of the moving rocks originate, coming from the southerly and westerly mountain slopes adjacent to the dry lake bed.

My

theory is that under very cold conditions, the water that accumulates here

in wetter conditions freezes, providing a protective and slick cover over

the playa. Then, under these conditions an occasional rock that dislodges

from the mountainside above the playa (i.e. erosion), rolls down at great

speed, hitting the ice, bouncing at first, and then sliding out at a

relatively high velocity. WIth the right type of tailwind, a rock pushed

into motion from the acceleration down the mountainside, continues sliding

until it hits water, and then mud of the lake bed as the water thins out.

There is enough acceleration at this point for the sliding rock to continue

on the still slick muddy surface due to inertia from the rocks mass and

speed to go on for some distance, leaving a track in its path. Eventually

the rock

stops due to the increased coefficent of friction of the mud versus that of

the ice or water. This is enabled by the fact that the water is

deepest at this corner of the lakebed, the same location where these rocks

originate, and thins out as you go further to the north and east.

My

theory is that under very cold conditions, the water that accumulates here

in wetter conditions freezes, providing a protective and slick cover over

the playa. Then, under these conditions an occasional rock that dislodges

from the mountainside above the playa (i.e. erosion), rolls down at great

speed, hitting the ice, bouncing at first, and then sliding out at a

relatively high velocity. WIth the right type of tailwind, a rock pushed

into motion from the acceleration down the mountainside, continues sliding

until it hits water, and then mud of the lake bed as the water thins out.

There is enough acceleration at this point for the sliding rock to continue

on the still slick muddy surface due to inertia from the rocks mass and

speed to go on for some distance, leaving a track in its path. Eventually

the rock

stops due to the increased coefficent of friction of the mud versus that of

the ice or water. This is enabled by the fact that the water is

deepest at this corner of the lakebed, the same location where these rocks

originate, and thins out as you go further to the north and east.

My theory is illustrated in the image at top. Note the path out of the water in

the distance, continuing in the mud for the latter half, and also note the

amount of mud that has accumulated as a crest in front of the rock,

eventually causing it to stop. The point is that rocks are already

moving very fast at the time they hit the mud of the playa, and not that

they start from a standing still position on the racetrack itself. This is

evidenced by the long streaking trail behind the rocks that we observe after

the fact.

The primary image on this page was photographed with a Canon 5D mark III, using a Canon Tilt-shift 24mm f/3.5 mark II lens. This is a remarkable lens for this type of photography due to the ability to tilt the focal plane. That allows sharp focus on both the foreground and background without having to excessively stop down the aperture, and risk image quality degradation due to diffraction limitations. It is probably the sharpest lens in my bag, but it is manual focus and requires more attention to detail and shooting on a tripod for best results.

You see more images of the Racetrack along with other images of Death Valley in my gallery here.

All content and images are property of Stephen Fischer Photography, copyright 2014. Last updated: 2/9/2014 ()